Hello! Thank you for joining me here on Substack. What Eliza Reads was conceived this time last year but it’s taken me a few months to find my voice and figure out how I can most add value. I squirrelled myself away in secret, posting privately for months, but I recently shared my accounts on my personal Instagram and am thrilled to have some friends join me here. This feels like the first time I’m writing for actual readers — how exciting!

I’ve always loved talking about books on my stories and it brings me so much joy when friends message to say they’ve loved a novel I’ve recommended or to ask what they should read next. There are so many people posting about books these days, whether on TikTok, Substack or more traditional outlets, so it’s a real privilege that you come to me for reading advice. Messages like the below make me feel like I have something valuable to share. I love that you trust my taste.

I want What Eliza Reads to feel like you’re getting a long text from a friend. It’s the natural evolution from years of sharing one- or two-sentence reviews on my stories, but the tone will remain the same. It’ll feel less anonymous than reading reviews online and more detailed than BookTok. You’ll get honest, unbiased (and often unfiltered) opinions from someone who knows about books.

My greatest joy is providing personalised advice to meet your reading needs. Whether you’re looking for a Christmas present for your mum, your next book club pick or the perfect reading list for a weekend mini break (stay tuned!), I’ve got you covered. As well as Instagram and Whatsapp, or wherever we usually discuss books, I’ll be here on What Eliza Reads whenever you’d like to chat.

In the spirit of sharing what Eliza actually reads, I’m diving into some big hitters this week. I hadn’t wanted to add to the many reviews about The Bee Sting and Intermezzo but several of you have asked for my thoughts on these two novels, so here they are!

Intermezzo

A new Sally Rooney novel is always a big event in the literary world, eagerly anticipated by readers across the literary-to-commercial spectrum. Known for their portrayal of complex relationship dynamics, full of repressed desires and struggles to communicate, her stories resonate with many. Her writing is self-aware, thoughtful and readable, but it’s not for everyone — I’ve had friends complain about the self-indulgent characters, absence of plot and lack of quotation marks. I get where they’re coming from, but that’s kind of the point. Her books are all about character, and the flat, spare prose takes us straight into her protagonists’ minds.

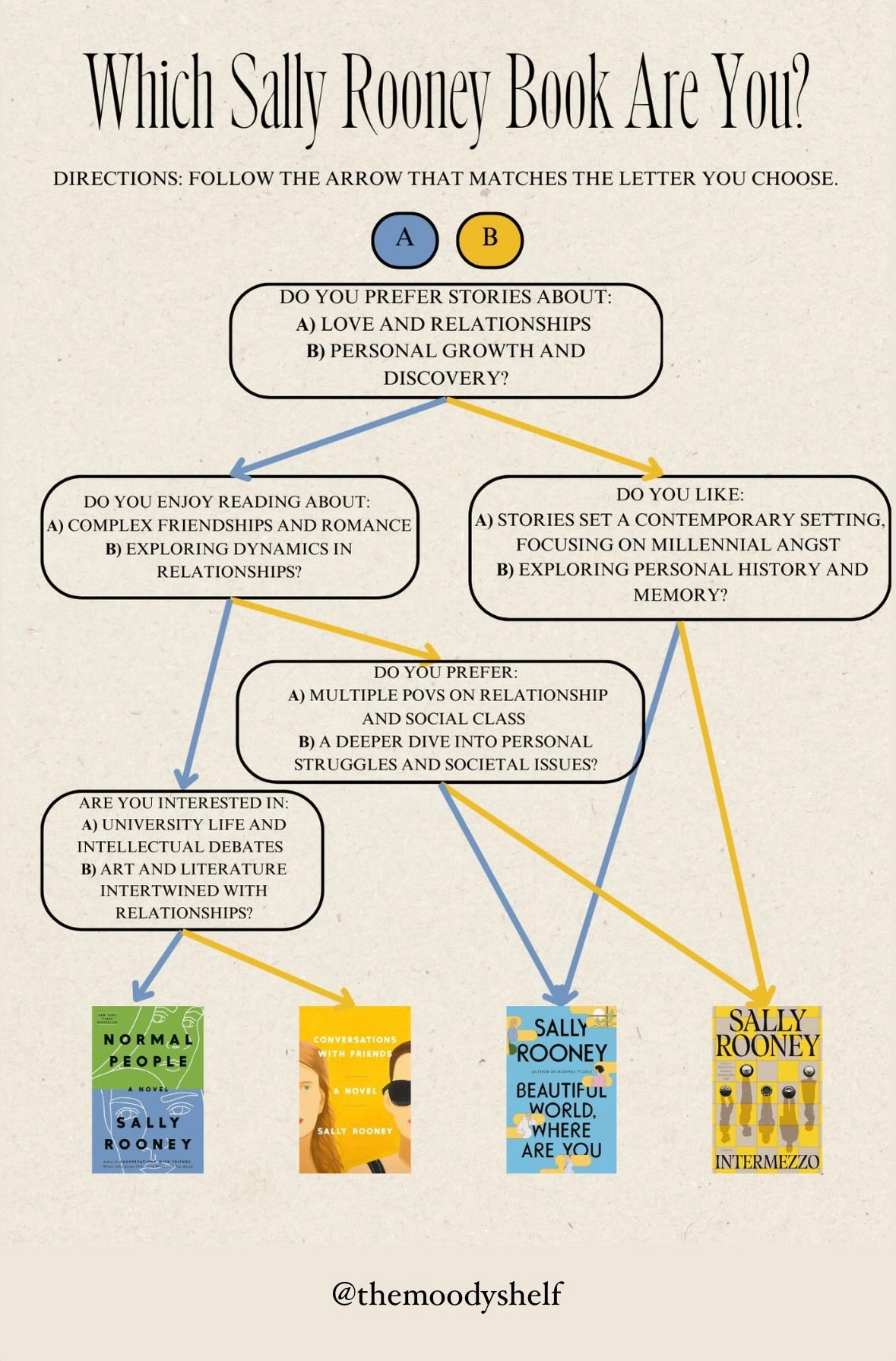

What I personally love about Sally Rooney is that there’s a pretty even divide between which of her four novels people consider their favourite. Normal People will always be mine; I can still remember reading an early proof in one sitting back in May 2018 and feeling completely understood, as well as the sadness and angst of 2020, when the TV adaptation first aired and the tension between Daisy Edgar Jones’s Marianne and Paul Mescal’s Connell struck a cord in the hearts of a locked-down nation. Though the adaptation of Conversations with Friends was widely seen as a disappointment (even though I enjoyed it, especially Alison Oliver and Joe Alwyn’s Frances and Nick), many friends consider Rooney’s debut their favourite. Several readers whose taste I admire love Beautiful World, Where Are You, which explores the relationship between two literary friends. Whatsapp discussions with two of my own talented friends are among my favourite ever conversations, Sally Rooney plays such an important role in our lives.

When Intermezzo first made its buzzy appearance this summer, with sought-after numbered proofs, the general feedback online was “I can’t share much just yet but this is Rooney’s best book yet”. There were tote bags and t-shirts for the first hundred customers who queued outside Bookbar early on publication morning and hand-drawn cover designs at the book launch. I was expecting this to be my favourite book of the year, and secretly hoping it would become my most-loved Rooney.

However, despite the initial hype, I’ve found that only a handful of my friends have read it, even two months after publication. I’ve had several people ask me whether they should bother, so I thought I’d offer my take.

If you’re a fan of Sally Rooney’s work, I’d say yes, it’s worth reading. Intermezzo departs from Rooney’s usual focus on romantic or platonic dynamics to explore the relationship between two brothers. It’s interesting to see her write from two very different male perspectives: the popular and successful lawyer Peter and the awkward, competitive chess-playing Ivan, who is nine years his junior. Set after their father’s death, the novel explores their individual struggles with grief and their inability to understand each other. Although this is the primary focus in Intermezzo, Rooney also explores the brothers’ romantic relationships. Peter, who is still somewhat attached to his ex-girlfriend Sylvia, is also involved in a sexual and financial dynamic with a college student called Naomi, who is the same age as Ivan. Meanwhile, Ivan falls for a 36 year old woman called Margaret, who he meets while he’s in Leitrim for a chess competition. Despite the obvious hypocrisy, Peter doesn’t approve of their age gap; the brothers’ disagreements about this situation put strain on their already tense relationship.

Rooney uses her signature pared-back prose to reveal the gaps between what the characters say and how they truly feel, underlining the brothers’ struggles to communicate. This is what she’s known for, and it’s why those of us who love her keep coming back, so I probably wouldn’t recommend Intermezzo if you don’t like this style of writing. I personally love how she uses interiority to explore the brothers’ differences, their individual anxieties, blocks and fears. Ivan is more literal than his older brother; his chapters are written in a stream-of-consciousness style and often involve repetition or clarification, as he seeks to understand the people around him.

It was the wrong thing to ask, he thinks. If he had just said nothing. Or if he had said something irrelevant, like going back to the cellist she mentioned, and asking what kind of music she likes. But no, he thinks: talking about music is never interesting. It doesn’t matter now. The reality is that he did ask, and she said in a doubting voice: We’re at very different stages in our lives. Why did she call him then? Just to get compliments from him, or what? Now, having had this thought, he feels terrible, because even to be liked by her to the small extent that she enjoys his compliments would be okay, but she probably doesn’t like him even that small amount.

Rooney perfectly captures the circling thoughts of an anxious, self-doubting young man. It’s so authentic! So intimate! The form is essential to the characterisation, making the reader fall more in love with sweet Ivan as the narrative progresses:

He feels impressed and humbled by the work his brain has done for him, humbled and impressed. Like, thank you, brain, wherever you are. A strange little room in his head where things happen secretly: which in fact seems so impressive it crosses over into being alarming.

Peter, on the other hand, is more socially confident, and the staccato style of his chapters reveal his ease around women and his “own social brilliance”. However, the short sentences and weighty words also convey Peter’s underlying struggles with himself, as he self-medicates and self-pities, frequently wondering if anyone would even miss him if he wasn’t there.

Depressed even thinking about it. Depressed in general probably. Thoughts rattling and noisy almost always and then when quiet frighteningly unhappy. Mentally not right maybe. Never maybe was.

Although they are both grieving and alone, the brothers struggle to see what they might have in common. The word intermezzo has several meanings: an unexpected chess move where one player disrupts the other’s plans; a short musical composition between two pieces of a larger work; an interval. The novel takes place at this juncture in the brothers’ lives, as they come to terms with their father’s death and navigate their relationship as adults. The title also highlights the games they both play, the black-and-white worlds of Ivan’s chess competitions and Peter’s legal career.

While there is a winner and a loser in a game of chess, in Intermezzo there may be some common ground. The tension between the brothers occupies the entire novel, but there is ultimately a sense of hope.

There is more to life than great chess. Okay, great chess is still a part of life, and it can be a vert big part, very intense, satisfying, and pleasant to dwell on in the mind’s eye: but nonetheless, life contains many things. Life itself, he thinks, every moment of life, is as precious and beautiful as any game of chess ever played, if only you know how to live.

There are some really moving passages, with the philosophical reflections and discussions on Beauty, Philosophy, Religion and Art that we have come to expect from Sally Rooney, and the ending is appropriately gentle and mature. That said, while we don’t come to Sally Rooney for the plot, even I found Intermezzo a bit slower paced than expected, so I wouldn’t recommend it if you’re looking for drama and motion (unless you count travelling between Dublin, Leitrim and Kildare). Unlike Normal People, where the will-they-won’t-they plot propels the narrative forward, I found the tension between characters in Intermezzo (Peter and Ivan, Peter and Naomi, Peter and Sylvia) more measured and thought-provoking.

Intermezzo is a mature, well-crafted novel which offers an unexpected perspective. While it’s neither my favourite read of the year nor my Number 1 Rooney novel, I would highly recommend it, especially if you’ve enjoyed her earlier novels.

Have you read Intermezzo? What did you think? Which Sally Rooney novel is your favourite?

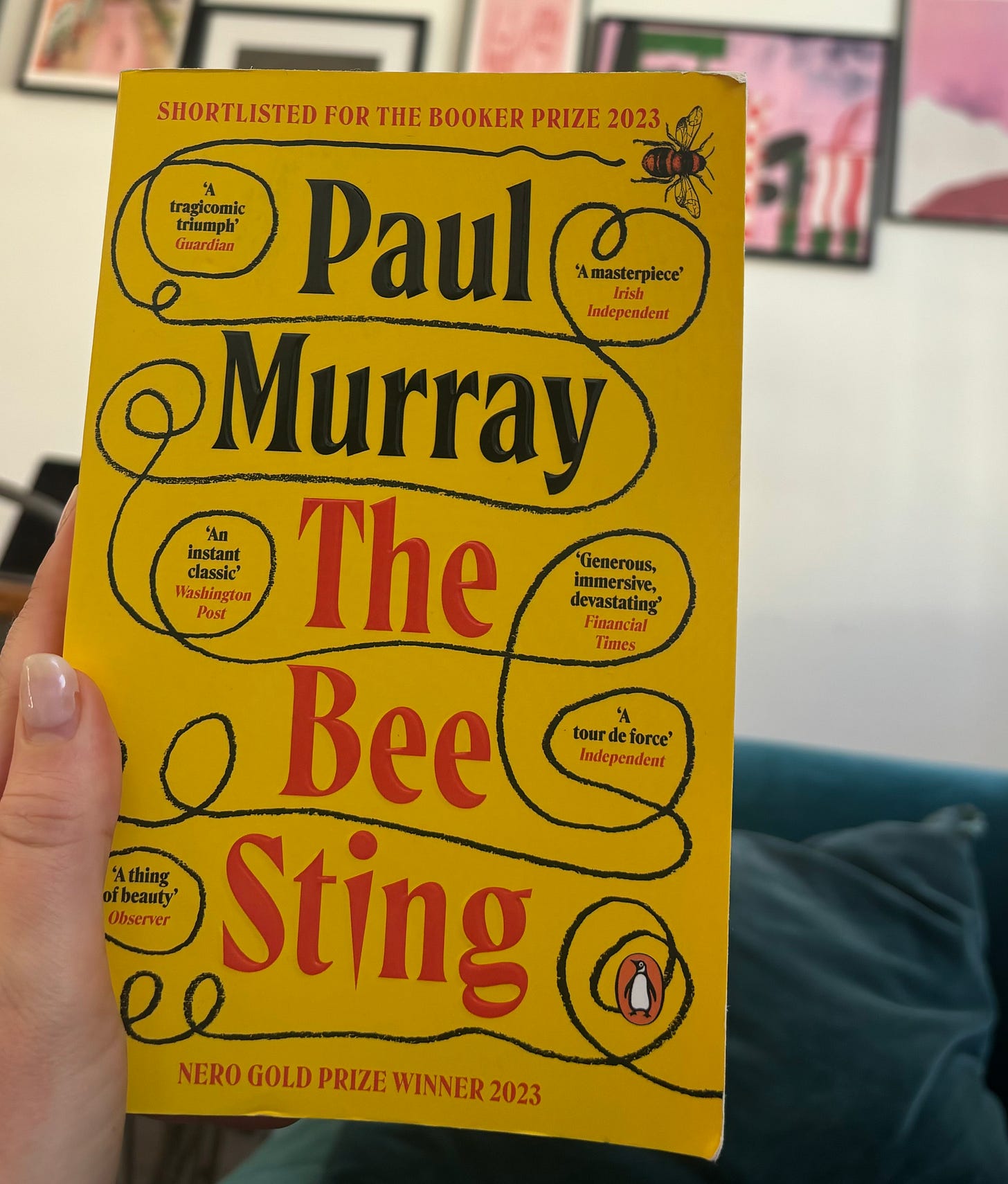

The Bee Sting

Unlike Intermezzo, I came to The Bee Sting relatively late. Winner of the Nero Gold Prize and shortlisted for The Booker Prize in 2023, this novel by the Irish writer Paul Murray is commonly perceived to be a masterpiece. It had been on my radar for a while but, at 650 pages long, I knew it would require both energy and commitment. I needn’t have worried: the 650 pages flew by. In fact, I would have gladly read another two hundred pages—I loved The Bee Sting that much.

The story begins with seventeen-year-old Cass Barnes, a teenager living in a rural Irish town. She finds her family infuriating, spends all her time with her bossy best friend and shifts her attention from books to boys as her exams approach — you know, classic teenage behaviour. The family’s car dealership is struggling after the financial crash, and Cass feels embarrassed by their precarious social position. She wants to keep up with Elaine’s spending habits and join her in Dublin for university; she doesn’t want to be seen as different in any sense.

The novel then shifts to the perspectives of the other three family members, each revealing a different dimension of the Barnes family’s past and their present struggles. There’s PJ, the 12-year-old brother who is largely ignored and just wants to be seen. Bullied at school for his father’s business missteps, he feels a deep responsibility to protect his family from their financial troubles and the looming threat of environmental catastrophe. We then hear from Imelda, the beautiful but shallow mother, gossips with her girlfriends and spends her husband’s money on clothes and trinkets, terrified of losing her social standing and returning to the poverty of her childhood. Finally, there’s Dickie, the downtrodden patriarch whose decisions often lead him into compromising situations, no matter how carefully thought out they are. Dickie’s story is arguably the most poignant and heartbreaking, connecting the novel’s many strands with a deep sense of pathos.

Murray conveys the characters’ personalities and unmet needs through their distinctive voices. I especially enjoyed Imelda’s chapters, where her lack of punctuation reflects both her poor education and her racing thoughts. PJ is intelligent beyond his years yet painfully naive. His chapters explore the gap between what he thinks will help his family and what they actually need, with a heavy dose of dramatic irony. This sense of miscommunication and isolation deepens as the story unfolds, as each character struggles with their own desires and limitations. Their isolation is heartbreaking as the dense plotting gains momentum and the family hurtles towards disaster.

The narrative structure is inspired: after four long initial chapters, we then meet each of the characters again in shorter, more intense chapters which continue their stories. Each one ends with a cliffhanger, keeping the reader racing through the other characters’ viewpoints to find out what happens, always fearing the worst. The pace increases even more in the final fifty pages, which are unlike anything I’ve ever read, the strands coming together in an unforgettable climax. While The Bee Sting deals with serious themes (climate change, abuse, class struggle, fate), these are explored with humour, pathos and impeccable observation. The novel is a masterful tragicomedy: tense and excruciating, but still a delight to read.

The Bee Sting is one of those books that demonstrates the true power of great literature. I haven’t stopped thinking about it since I finished. It’s the kind of novel that leaves you with so much to unpack, and I immediately turned to the internet to verify my theories and read others’ insights. You can’t talk about it too much without spoiling it for others, leading to whispered discussions and impassioned statements of ‘THIS BOOK!’ whenever it’s mentioned. This is what reading is for, in my opinion.

If you love family drama, complex characters and alternating perspectives, I absolutely recommend this book. If you’re planning to read it soon and want someone to discuss it with along the way, please let me know. I could honestly talk about The Bee Sting for hours!

Extra reading

If you’re a nerd like me, you may be interested in these (more analytical) pieces on Intermezzo I enjoyed in September and October:

The Common Reader on neurodivergence in Intermezzo

Martha’s Monthly’s review of Intermezzo

twenty-first century demoniac on Sally Rooney’s interview at the Soutbank Centre

Soul-Making on Sally Rooney and the history of the novel

Hmm that’s interesting’s review of Intermezzo

If you’ve got this far, thank you for reading! I’ve got a few reviews to go up on my Instagram this week, and I’ll be back next week with another post.